Facebook and the Internet

Social. Private. Open. Pick two.

This is the title of a post by jez. I’ve mentioned him a few times at this point now on my site, and it’s because I have a lot of admiration for him. He was an upperclassmen at my school who I never really got close to or talked to (when I was a freshman, I was pretty shy and intimidated by all of the incredibly smart people at CMU), but he was my TA for 15-131 Great Practical Ideas for Computer Scientists and left an impact on me. Anyways, he has some very thought-provoking essays and well-written technical articles.

I got kicked off of Facebook for no clear reason today

Full disclosure: I’m angry. I woke up this morning and checked my phone and had a few messages from my friends that were sent while I was asleep. I responded to them, one of them being particularly personal and somewhat urgent to respond to, and noticed that none of my messages were sending. I tried turning off my WiFi to instead use cellular data, but again, no luck. I did a brief look online at Facebook’s server status, saw not much that was out of the ordinary, and decided to move on without much additional thought. It’ll eventually send, I thought to myself. I’ve had issues with my messages being extremely slow or failing to send several times in the past, and figured they would make it through eventually.

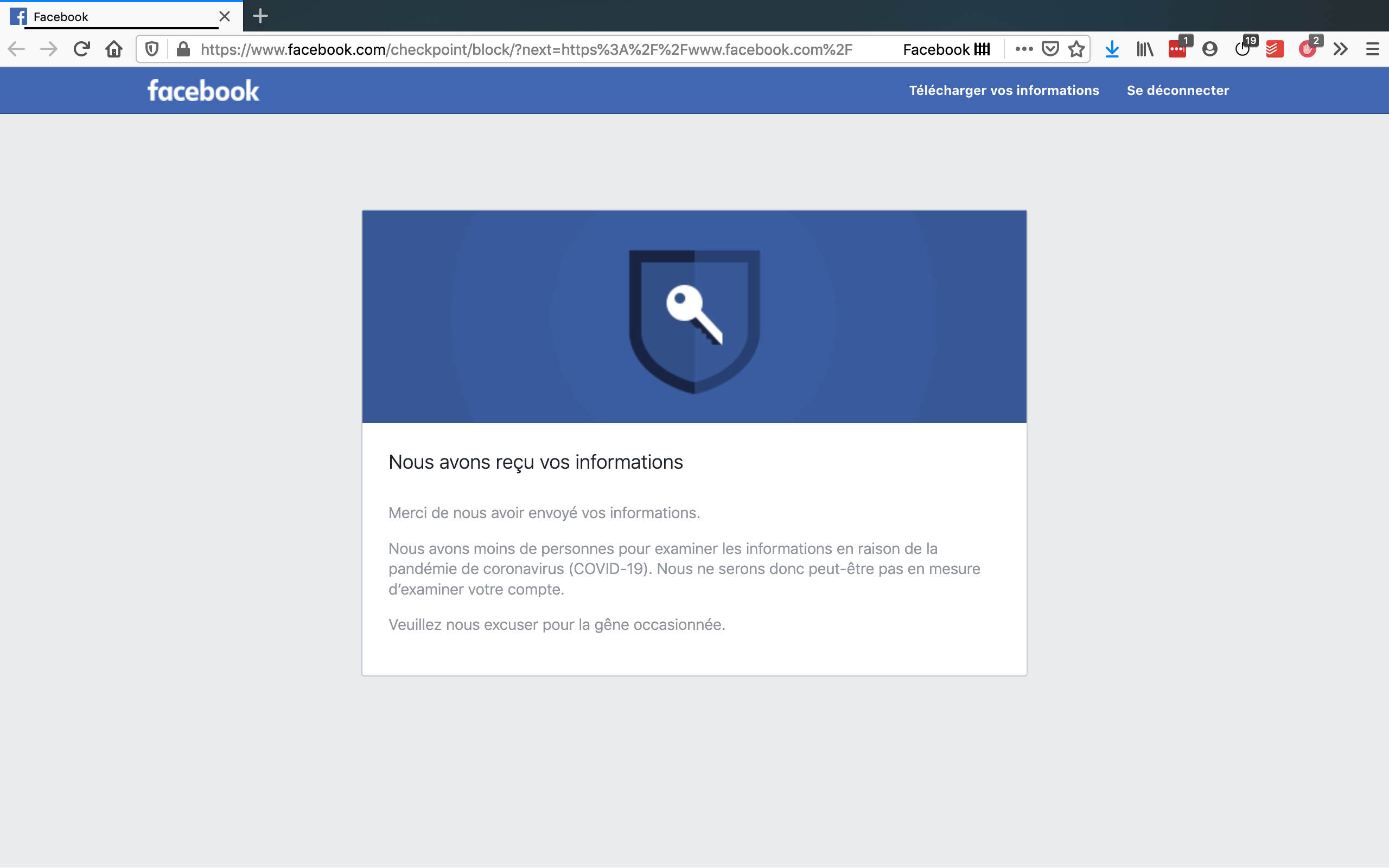

Then I checked my Facebook. Or rather, tried to. When I opened the app on my phone, I was informed that my account had been removed for violating community guidelines and I could fill out a form to repeal the process. I did this (which included uploading a video of my face looking in different directions – left, up, and to the right) and then was met with a screen that simply said they had received my information and that because they had fewer people available due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, they might be unable to review my appeal.

So. As of writing this, I no longer have a Facebook account at all. I’m mostly upset at the sudden loss of Messenger – I’ve deactivated my Facebook account many times in the past, the longest being an 8-month stretch in 2019, but have never left Messenger. It’s always been my primary way of contacting others, and the sudden eviction from the space left me a bit unsure on what to do next. I have an option to download my data, which I’ve put a request in for and am currently waiting for the email to let me know that it’s ready for me.

To be honest, I’ve thought for a while about wanting to delete my Facebook. I’ve done various intermediate steps, and the closest I’ve been is deactivating Facebook while keeping Messenger. But I’ve never quite pulled the plug, for a number of reasons I just haven’t yet brought myself to overcome. For one, it was convenient and natural to find people that I had met in-person on Facebook simply by using their name: no email address or phone number needed. Just a quick check of their profile picture (that’s looks like what I remember) and mutual friends (a lot of my classmates are their friend, and I met them them at school) was enough to make sure it was the right person. I also was highly involved in extracurricular activities in both high school and college and lead a number of them, and we would coordinate all of our group activities and announcements through Facebook groups. It was also then exceedingly easy to message somebody or start a video call if you needed a quick chat or to sync on an issue. You almost couldn’t run for an officer position in a school organization without having a Facebook profile.

I’m no longer in school, so those reasons are all mostly gone. I considered deleting my Facebook after graduating, but I considered otherwise after my boyfriend at the time had said it was nice to keep around for people to reconnect with me. I disagreed, and had said that I didn’t think there was much use from conversations with people whose paths I wouldn’t otherwise cross again with except for an errant like. I graduated early, and didn’t tell many people about it. It wasn’t until I was at Fuku Tea and ran into a former student of mine, and as we caught up, I told her I was graduating and would be leaving in about a week, that I changed my mind. Her face immediately became crestfallen, and she cried and told me how much she’d miss me – and also she was upset that she had no idea! I immediately felt pretty terrible, and ended up posting on Facebook that I was graduating and chatted with a number of people who had also drifted off from my mind but I still actively cared about. And it was nice. And in that moment, I was happy I had kept my Facebook profile. Those were interactions I am grateful to have had, and I had them because of Facebook.

When I was booted off of Facebook today, I was in the middle of some (at least to me) relatively important conversations. A friend had just been laid off from Uber, and we had been reaching out to people to try to see if their company was still hiring in the pandemic and possibly seeing if they could refer him. Most of these people aren’t people I’m particularly close with, and so I don’t have another way to reach them aside from Messenger (no phone numbers, emails, or other platforms). And then, my ex-boyfriend from earlier in college had messaged me with something where he was feeing nostalgic and sad, and I had wanted to send him a comforting message. Telling him that I understood, and despite feeling the way he was, it was good that he was processing those emotions. But all of those messages just had the “pending” icon next to it, and when I reached out to some mutual friends on other platforms to let them know what was going on, most of them had thought I had just inexplicably blocked them. I’ve been critical of Facebook for a while, but the abrupt ending of several ongoing conversations left me flailing and a bit lost.

I virtually never post on Facebook – the last update I made was announcing that I had graduated in December 2019 (and changing some profile pictures and cover photos). The only other activity I have is tagging friends in memes, and responding to tags. That’s it. I was confused. And I was given absolutely no explanation.

And then I was angry.

The criticisms I have of Facebook – and big tech and other Internet spaces in general

I mentioned that I’ve long been hesitant about Facebook. But I stuck around. Convenience. It was important for extracurricular activities in school. The stickers are cute. There’s also a number of half-way measures that give you an illusion of reclaiming a bit of your digital presence while still maintaining the things that you didn’t want to lose from quitting the social media conglomerate completely, such as the deactivation feature (and separation of Facebook from Messenger in that regard). But there were a number of things that I wasn’t really comfortable with, and so maybe in a strange way, getting inexplicably kicked from Facebook was what I needed to finally face what I was uncomfortable with and consider jumping ship.

Privacy and general ethics

To start with, Facebook is an incredible abuser of privacy. Facebook’s ad-based revenue model involves, like many other technology companies, carefully tracking its users’ behavior both on and outside of the site. Facebook became one of the most valuable companies in the world by perfecting the most successful system for meticulously purveying and collecting user data. It’s no longer surprising to Google for an item and immediately start seeing ads for that item in your Facebook feed or on Instagram (which is also owned by Facebook). And while dodgy privacy records are nothing out of the ordinary in this world, there are a litany of things that tilt Facebook into its own league privacy violations. This article does a far better job than I ever could on chronicling why exactly Facebook is problematic.

Instead, I just want to talk a bit about why we should care about privacy. Even if you think you have nothing to hide, you should care. I’d also like to quickly stress the difference between secrecy and privacy. For example, let’s use me wanting to go to the bathroom. It is not a secret what I will do in the bathroom. But, privacy is the ability to hide what I am doing in the bathroom from the public eye. Perhaps there are things that do not need to be a secret, but that does not detract from your desire to hide (or have the power to) that information. I remember seeing a number of trailers for movies or shows with a theme of a society built around time (one’s remaining lifespan) as currency. They all have cool animations and show usually these digital tattoos on people’s wrists which display the amount of time they have left to live, and it can be spent in mundane situations (one scene showed people waiting in line and paying five minutes for their daily mocha latte) or be given directly to another person. These shows almost always have this dark undertone of exploitation and eternally young, evil, rich, and powerful people haughtily going about their day while the powerless lurk in society’s underbelly, forgotten, and with tragically short lives left ahead of them. I know this is an incredibly dark tangent, but it’s a bit about how I feel about privacy. It’s a commodity that people take so easily for granted, much like one might consider five minutes of their lifespan, but it’s incredibly important. But trading privacy for convenience is a transaction many of us, including me, regularly make in our lives without a second thought. And it’s something that generally only those who are on the extremes of society have, either the very poor and underprivileged who never had a digital presence to begin with or the upper-class and erudite that have the means and knowledge to reclaim their digital identities online.

Privacy is fundamentally important because it enables autonomy. The ability of an individual to express themselves selectively by controlling or secluding information allows us to self-determine and control the image that exists of ourselves. Without privacy and without this power, our identities are essentially out of our control and completely at the mercy of others. The reason why we should care about information about ourselves being in the hands of others is because we cannot always trust others to be good actors with our data, and with allowing bad actors to seize our information, we are also ceding parts of our ability to assert ourselves. And even if you supposedly trust the entity to whom you’ve relinquished your data, there’s been massive large-scale data breaches at Facebook which have revealed sensitive information about you to potentially nefarious third-parties. Companies that don’t take all of the measures they can to avoid data breaches are simply irresponsible, and data security is unfortunately often left behind. When Scott Krulcik, another outstanding upperclassmen from CMU, passed away suddenly, Prof. Jean Yang wrote in a tribute to him something that made me see privacy differently:

He (Scott) talked about trying to be a good human who wants to help other humans and explained the connection with computer security. In his words, if he’s producing software that helps people in some other way but leaves them vulnerable to identity theft and blackmailing, then the software isn’t really helping people. Here, I thought, was a student who really got it.

Facebook has also committed several serious privacy breaches even without data breaches to accidentally expose your information to third-parties, including selling your endorsement to advertisers and politicians, tracking things you read on other parts of the Internet, and they also used to actively prompt other users to snitch on friends who are not using their real names (links are compiled from Sal’s article mentioned earlier). All of this is for an intricately detailed portfolio of you that’s startlingly accurate, from your political views, age, gender, and sexual orientation, which they then reveal to third-parties that include various companies, governments, and advertisers.

This widespread dispersal of your information can actively harm you. We’ve all heard the story of the teenager that Target figured out was pregnant from her purchase history. But it needs to be more firmly stressed that there is virtually no limit to what these companies can figure out about you – and while it may seem innocuous (if not a bit creepy) for a company to be able to discern your race, your health status, and whether or not you’re pregnant, when combined with the fact that Facebook and other companies are actively selling your information to third parties that include institutions that affect you, this is problematic. Would you like to be denied health insurance because of a company determining that you were likely to start having health problems? What if information about whether you’re pregnant reached a prospective employer (an example which quickly comes to mind is the Google memo last year alleging pregnancy discrimination)? Facebook has also selectively not shown housing and employment ads based on race in the past. We’ve also heard several stories about the police or SWAT teams getting involved erroneously based on Facebook activity, and so while law enforcement already has a record of acting in error, these tools only further inflame those instances. Facebook data is also delivered directly to the PRISM program – government surveillance fueled by social media sites is already ongoing (and for reasons as to why a surveillance-state is suboptimal, there are multitudes of people online who put it better than I ever could, aside from a read of George Orwell’s 1984). This is more than just hypothetical musing. These privacy abuses have real-world consequences that can actively harm you, and are becoming tools to perpetuate continued disenfranchisement of various populations but at an alarmingly efficient pace.

Building communities and bringing the world closer together

Facebook’s mission states that they aim to “give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together”. Facebook is aware of how powerful of a presence they have become. It’s extremely pitiful how little they have done to protect those on their platform and stay true to their mission despite knowledge of how widespread their reach is. I won’t delve into the entire debacle that was the 2016 United States presidential election and Facebook’s involvement with Cambridge Analytica, but fake news is a problem that all Internet spaces have a serious problem with (including Reddit, Twitter, etc.). But that being said, mass media so far has served little but to create increasingly insular, polarized, echo chamber communities driven by poorly-cited sensationalist news articles. And these groups are destroying communities and driving the world even further apart.

I wanted to talk more about my general beliefs about the Internet later in this post, but I did want to reflect a bit on how as a Chinese-American struggling with her identity in middle school, I admired how the Internet had been a beacon of democracy – a mobilizing, powerful force – in times like the Arab Spring and Hong Kong protests. And to see how far it had fallen greatly pained me. People at Facebook had blown the whistle for years (and have been dismissed or left) about potential abuse by those with a political agenda on the platform, and the even greater danger such attempts had given the incredible fan-out factor social media sites have with sharing ideas. People at Facebook had to have known that their site was an immense expanse of kindling ripe for ignition into an uncontrollable inferno, and that smaller fires had already been erupting without serious public attention. And it’s a hard problem. I have sympathy for that. I spent much of my freshman and sophomore years in college doing research in CMU’s eHeart Lab looking at the problem of moderating spaces on Twitch and Reddit, and while I’m far from being an expert, I remember at times having moments of brief despair at the problem’s intractability. But it’s a problem that’s still their responsibility, and it’s inexcusable that it wasn’t taken seriously until it had serious impact on the United States’s presidential election (and while interference into one country’s political elections by others is far from being a precedent, it’s notable because it was the United States – which also says something about which countries and political systems we care about). I’ve had a lot of people tell me that elections aren’t a huge deal, but they are – peoples lives are at stake. Whether it’s judicial decisions that establish laws that might harm you, escalations that bring you to the brink of World War III, callous approaches to nuclear proliferation and general diplomacy, or the calling of air strikes that kill innocents, there’s a lot at stake when electing a Commander-in-Chief.

But also at its core, Facebook is a place for friends and family to connect. I still have no transparency as to why or how my account could have been deleted (I virtually never post or interact with others) and I was given no specifics as to which community guideline I “violated” with my sparing engagement with the platform. Facebook has still been a valuable part of many people’s lives, including mine. And Facebook knows this. After looking on other online platforms like Reddit and Twitter, it’s not just me who has experienced an erroneous removal of my account – and with this, Facebook is removing the ability to connect and share content with loved ones. A mistake is not enough justification. Especially in a time like this, where the world has come to a standstill amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and human connection is as precious a resource as ever, this is unacceptable. One of the most plausible explanations for what happened is likely an automated account filtering algorithm that went a bit trigger-happy, but algorithms bear no sense of culpability – only their creators do. We developers frequently have to make conscious decisions about what to prioritize in the algorithms that we write and the ramifications those decisions have. To make the decision that false positives are acceptable to the scale that they are doing, in a company with engineers as talented as those at Facebook, when dealing with things as important as people’s Facebook profiles (which have become instrumental pillars in our social structures), and in a time where social connection is as pertinent as ever, is inexcusable. While this possible explanation for what happened is just speculation (everything really is speculation in terms of how the account deletion happened, because there is no transparency in the process), and there’s a bit of credit if this is indeed an attempt by Facebook to correct for its fake bot problem, making an algorithm that’s overzealous is valuing ridding a fake bot more than preserving a legitimate user on Facebook’s potentially only tool for social connection at the moment.

At a time when the world is as far apart as one could imagine it to possibly be, this seems rather disingenuous to Facebook’s mission.

Digital ownership and autonomy

But this entire event has also been a jarring reminder of how our digital presence is owned by just a few companies, and how easily we can be eradicated. Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp are owned by Facebook. Google owns Gmail and YouTube, as well as a whole suite of office and productivity tools, and Microsoft owns LinkedIn and GitHub. Twitch is owned by Amazon. And in a mistake like what happened to me earlier today, an entire pillar of your digital identity can disappear. This gets somewhat entangled and related to DRM and digital tenancy – that despite purchasing goods on Amazon, Netflix, Spotify, Steam, and other platforms, we don’t actually “own” any of it and most end user agreements stipulate that any and all of it could theoretically disappear or become unavailable at anytime and there’s not much you can do about it. But, the point being that much of our digital presence is completely out of our control and at the mercy of several large companies that exploit our data for their profit in ways that could seriously harm us, and much of what we do own is more akin to temporarily renting a space as opposed to true ownership. We don’t control our digital lives. While it’s convenient and we enjoy many things as a result of this trade-off, it’s somewhat disconcerting that an entire part of our identity is essentially no longer something that we have autonomy over.

For a better Internet

I know, I know. There’s a lot of things I’ve said so far that are hypocritical – and again, these criticisms are not just limited to Facebook. And a lot of these companies have done quite a bit of good for the world as well. And I’m definitely not saying that all of these companies don’t provide any value (or provide negative value). But there are some seriously problematic records on many of these companies that we should not be excusing so easily. Perfect is the enemy of good. That these issues are not unique or that alternatives might also be problematic doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be meaningfully engaging with them. Going a shade of gray in the right direction is still progress.

Some time when I was in middle school, I read John Perry Barlow’s Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. I’m an idealist when it comes to the Internet. I believe in the Internet being a space that transcends national borders and militaries. A world where everybody intrinsically has a place. A place where anyone can express their beliefs without fear of repercussion or being coerced into conformity. A place where concepts of sovereignty, property, identity, distance, and movement are meaningless.

We will create a civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace. May it be more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.

Barlow wrote this in 1996, before I was even born. I stumbled across his writing when I was an angsty middle school kid who was wrestling with her identity, one of the more confusing ones being my status as a Chinese-American. And the pride I felt for both identities, but also some of the shame. I was young and immature, and highly impressionable. The first time I understood what corruption was and what it looked like, I was angry. I was angry at the city officials I had met in China, at the times that were retroactively explained to me as misappropriated government funds, and at the summers I’ve spent at my maternal grandparent’s place. And those memories that I made there previously were fond ones (although I always hated that I had to bathe using a bucket of water, especially if I wasn’t the first one to wash up that day), but now they were twinged with fury as I became aware of their poverty and compared my time there to the gluttony I had witnessed just earlier in our trip. I was equally as angry when I learned about the United States’s hypocrisy and involvement in the Middle East, destabilization of the region, deposition of leaders, and war crimes that all had been fueled by American hegemony.

I was an edgy and angsty kid. But then I learned about the Arab Spring. I learned about how the web had been a weapon of resistance, an arbiter of justice, a mobilization tool for the powerless in pursuit of equality and what was right in the world. I learned about protests in Hong Kong and the role the web had played there as well. The web was almost a romantic idea to me, and I was in awe of its power.

This article, ‘The Web We Have to Save’ is written by Hossein Derakhshan and I highly recommend reading it. I first saw the article from jez’s post, and in it, the author gives his perspective on how the web had evolved in the 6 years that he was jailed in Iran for being an open web advocate. The author talks about a time that seems so stark to what the Internet is as I know it now, and it made me reflect back on my middle school self and what she would think about the state of the world today.

Sometimes I think maybe I’m becoming too strict as I age. Maybe this is all a natural evolution of a technology. But I can’t close my eyes to what’s happening: A loss of intellectual power and diversity, and on the great potentials it could have for our troubled time. In the past, the web was powerful and serious enough to land me in jail. Today it feels like little more than entertainment. So much that even Iran doesn’t take some — Instagram, for instance — serious enough to block.

I miss when people took time to be exposed to different opinions, and bothered to read more than a paragraph or 140 characters. I miss the days when I could write something on my own blog, publish on my own domain, without taking an equal time to promote it on numerous social networks; when nobody cared about likes and reshares.

That’s the web I remember before jail. That’s the web we have to save.

There was a time where consumption wasn’t in a stream fueled by likes and shares. The hyperlink was powerful and sought after, and reading was complete and responses were measured. Of course there were trolls, but nothing in comparison to the beasts we have today (what immediately sprouted into my mind were the modern Gods from Neil Gaiman’s American Gods – they’re well-worshipped today).

That’s a web that I’d also like to save. While having my Facebook account suddenly deleted has been an interesting if not rather amusing way to be reminded of some of the beliefs I have, it gives me some time to contemplate about what’s next. I have some thinking about what to do when (if) my account gets returned to me.